Contents

I’ve traveled to Berlin to stare into the future. Or, more accurately, I’ve traveled to Berlin to stare – literally stare – into a device that some see as our best hope for taming, and perhaps harnessing, the future powers of artificial intelligence (AI). Others see that same device as a “Black Mirror” episode sprung to life, designed to track and control us.

I’m staring into “the Orb.”

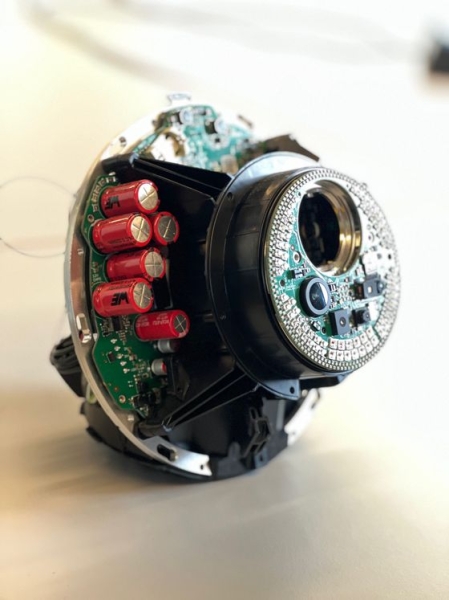

The Orb is about the size of a bowling ball. It’s chrome and shiny and smooth. I’m instructed to move closer and stare into a black circle, like how you peer into a machine at the optometrist’s. The Orb then uses a system of infrared cameras, sensors and AI-powered neural networks to scan my iris and verify that yes, in fact, I am a human being.

And I’m hardly the first to do this. There are now over two million humans who have stared into the Orb, the flagship device from Worldcoin, the crypto-meets-AI project co-founded by Sam Altman (CEO of OpenAI) and Alex Blania, who is now the CEO of parent company Tools for Humanity.

Worldcoin has an audacious premise: AI will continue to improve and eventually evolve into AGI (advanced general intelligence), meaning it’s smarter than humans. That will spur leaps in productivity. This will create wealth. And instead of that wealth being snatched by elites, it should be fairly distributed to all of humanity – literally everyone – as a form of UBI, or universal basic income, which will empower billions. That UBI will come in the form of a cryptocurrency. That crypto is Worldcoin (WLD).

The merits of UBI have resonated with Altman for years. “UBI is interesting to me even without talking about AI,” Altman says in a recent Zoom interview. “It’s an idea that appeals to a lot of people. If we have a society rich enough to end poverty, then we have a moral obligation to find out how to do that.”

So maybe the magic of AI can succeed where the mud of politics has failed? “In a world of AI, [universal basic income] is even more important, for the obvious reasons,” Altman says, who added he still expects there to be jobs in a post-AI world. “But, A, I do think we’re going to need some sort of cushion through the transition, and, B, part of the whole reason of being excited about AI is it’s a more materially abundant world.”

Worldcoin, following this logic, could be the key to unlocking that abundance. But there’s a catch. If the goal is to freely give out tokens to everyone, in this AI-enabled future, how can we be sure we’re handing out the loot to a human, and not an AI-powered fake? (It’s only a matter of time before AI can laugh at CAPTCHA.) Or what if bad actors use AI to create multiple wallets and game the system?

The team thought about the problem. They thought about all the ways humans could prove they’re actually human. And after considering all the options, they came to a wrenching conclusion. They didn’t like it. “We really did not want to do this,” Blania says. “We know it’s going to be painful. It’s going to be expensive. People think it’s weird.”

They decided they had no choice. It was unsettling and controversial and the optics are literally the stuff of nightmares, but they thought it had to be done: They needed to verify humanity with biometric data. Blania is talking, of course, about the Orb. “For a number of reasons, we didn’t want to go down that path,” he says. “But it really was the only solution.”

This is the untold story of that solution, and a journey to discover if it’s a solution or a problem.

The Orb

The Orb is sleek and minimalist, with no visible controls or knobs. It looks like something you’d buy in an Apple Store. That’s not a coincidence, as the Orb’s lead designer is Thomas Meyerhoffer, who was Jony Ive’s first hire at Apple. (Ive is the legendary designer of the iMac, iPod and iPhone.) The Orb was meant to evoke simplicity. “It must be simple enough to speak to all of us. Everyone, all around the world,” Meyerhoffer once said.

In the Berlin office, Blania shows me older models of the Orb and tells me stories of the company’s early days, when they first tinkered with the hardware. The idea was originally conceived as “the bitcoin project,” with the goal of freely distributing bitcoin to people once they proved their humanity. Blania holds up an older version and chuckles. It has a slot that spits out physical coins, almost like a reverse piggybank. It has two eyeballs and a mouth.

The early Orbs even talked to you. “This thing screams at you in a robot voice,” Blania remembers now, amused by the nostalgia. He explains that each of the early Orbs could hold 15 physical coins (which contained the keys to actual bitcoin), and the idea was that people would take the cryptocurrency more seriously if they held something in their hand. (The team soon scuttled this idea for obvious reasons.) “We just tried so many things,” says Blania, such as making the Orb vibrate when it told you something. Every week they cranked out a new version of the Orb, using 3D printers to quickly iterate.

Blania is a tall, athletic, baby-faced 29-year-old wearing jeans and a t-shirt. He’s an unlikely CEO. He leads one of the most ambitious projects on the planet, but this happens to be his very first job. Altman tapped him to be CEO and co-founder after his stint at CalTech, where he researched neural networks and theoretical physics. Blania admits that in the beginning, “other than technical depth, I think I was a bad CEO.”

So Altman gave him help. “Sam basically gave me a couple of people that I met with every week,” he says. “They basically told me, every week, the ways in which I was doing a bad job.” One of these CEO coaches was Matt Mochary, who had previously coached both Altman and Brian Armstrong. They tutored him on the managerial basics like how to conduct one-on-ones, how to run staff meetings and how to handle public speaking.

Blania has no hobbies, unless you count weight-lifting and meditating. He splits his time between San Francisco and Berlin (Tools for Humanity’s two main offices), and when in Berlin he starts his day at 9 A.M., leaves the office at 10 P.M., and then he hits the gym. “I try to work every waking hour.”

The work includes leading 50 full-time employees, and some were tasked with creating a new crypto wallet from scratch. “The crypto user experience is very rough,” says Tiago Sada, head of product and engineering, who I also meet in the Berlin office. Sada is yet another genius (there’s a lot of those in AI circles). He grew up in Mexico and built robots with his friends when he was 14 years old, then launched a “Venmo for Mexico” startup and later met Altman at the Y Combinator incubator.

Sada was initially skeptical of crypto because, in his view, it was hard to get non-technical people to easily sign up. When he asked people to do things like download a MetaMask extension, they were lost. Sure, crypto wallets were effective for the crypto-curious, but they were a non-starter for many of the planet’s eight billion people. And a core idea of Worldcoin is to get cryptocurrency to everyone, easily, regardless of their tech savvy. Something they could do without complications. Something they could do, literally, in the blink of an eye. So they built WorldApp, which syncs to the Orb and allows for near-instant onboarding.

I tried it out myself. In the Berlin office I downloaded the World App from the App Store. The app synched to the Orb, which sat on a conference room table. (I had imagined the Orb would be sitting on some pedestal in a throne room. Alas.) Seconds after, I stared into the shiny globe, my account was verified and I was now the proud owner of 1 worldcoin*. (*This would not have been possible had I tried in the U.S., where they are not rolling out tokens – at least not yet – for regulatory reasons.)

The onboarding process, at least for me, was buttery smooth. It was easily the most frictionless crypto onboarding I’ve experienced in my five-plus years covering the space, if you’re willing to overlook the whole scanning-the-eyeball thing. (More on that in a bit.)

One reason the tech works so smoothly is an embrace of AI. And the paradox of AI is everywhere. The potential consequences of AI – both wondrous (productivity gains) and malicious (deep fakes) – fuel the company’s mission, but on a more day-to-day basis, the recent gains in AI have made the engineers more efficient. “Worldcoin would not be possible without AI,” says Sada. Multiple machine learning models help power the guts of the Orb, and Sada says that the AIs have (in effect) begun to train other AIs, further supercharging their productivity.

And how do AIs train AIs?

“People think that we need a lot of data to train the algorithms,” says Sada. “Actually, what a lot of these models allow us to do [is] generate synthetic data.” Just as you can use AI image generator Dall-E to create an image of Luke Skywalker dunking a basketball in the style of Caravaggio – and it comes back in seconds – the engineers can use AI to create data simulations. “That allows us to use significantly less data,” says Sada. “That’s why we’re able, by default, to delete everyone’s [biometric and iris] data.”

I get the appeal of framing the story as ‘creating the problem here, solving the problem there.’ That’s not how I think about it

That brings us to the uncomfortable question that has dogged Worldcoin since its inception: Just what, exactly, is Worldcoin doing with these eyeball scans? As soon as Altman The Orb via Twitter in October of 2021, critics and skeptics pounced. “Don’t catalogue eyeballs,” admonished Edward Snowden in a . “Don’t use biometrics for anti-fraud. In fact, don’t use biometrics for anything.”

Snowden acknowledged that the project used zero knowledge proofs (ZKs) to preserve privacy, but insisted “Great, clever. Still bad. The human body is not a ticket-punch.” As my CoinDesk colleague David Z. Morris wrote, it’s “spectacularly and inherently risky for a private company to gather this kind of biometric data about everyone on Earth,” and that, by the way, calling the device the “Orb” – with heavy overtones of the eye of Sauron – is “creepy as hell.”

Blania, Sada and others from Worldcoin conveyed to me many, many times that the Orb is not collecting biometric data from the eyeballs, or at least not unless the user explicitly allows it. “Privacy is a fundamental human right. Every part of the Worldcoin system has been carefully designed to defend it, without compromise. We don’t want to know who you are, just that you are unique,” reads the company’s privacy statement. (That said, some data is captured if the user allows it. The default setting is to not capture data; users can change this and allow it to be stored, which Worldcoin says is used for the narrow purpose of improving its algorithm. Why users would go out of their way to enable this is beyond me.)

“The really cool thing, and the really hard thing,” says Sada, is that the Orb handles all of its calculations and verifications locally to vet that you are a unique human, and then it generates a unique “iris code.” Think of your World ID as a passport, says Sada, and all the Orb does is stamp your passport to say it’s valid. He stresses again that no map of the eyeball is captured. It’s just a code that says you are a unique human – not your age or race or gender or eye color.

(On the day of Worldcoin’s public launch, Ethereum creator Vitalik Buterin wrote a detailed blog post that interrogated its claims of privacy. He flagged concerns but gave it decent marks. “On the whole, despite the ‘dystopian vibez’ of staring into an Orb and letting it scan deeply into your eyeballs, it does seem like specialized hardware systems can do quite a decent job of protecting privacy,” he concluded. “However, the flip side of this is that specialized hardware systems introduce much greater centralization concerns. Hence, we cypherpunks seem to be stuck in a bind: we have to trade off one deeply-held cypherpunk value against another.”)

Once users have their WorldID – which Worldcoin insists is privacy-preserving – it can be used, in the future, as a sort of skeleton key to access other apps and websites, such as Twitter or ChatGPT. They’re already dabbling with this functionality. WorldID recently announced integration with Okta, a German identity and access management provider, and more partnerships are in the works.

WorldID is a form of self-sovereign identity (I did a deep-dive on SSID a while back), which is itself a holy grail for many in the Web3 space. In the rosy and best case scenario, the Orb could enable the scaling of SSID and UBI to billions of people – wresting online “identity” from the centralized corporate titans – and help give poorer, marginalized communities greater access to financial empowerment. That’s the vision.

But who pays for this? The way the system is currently configured, once you’ve signed up for the Orb, every week you can claim 1 worldcoin. That’s the early kernel of UBI. Who’s footing the bill for this token that will suddenly appear in the wallets (or eyeballs) of everyone on the planet? On the one hand, sure, there’s precedent for cryptocurrency that enters the world as if by magic, and then eventually accrues value. Exhibit A: Bitcoin. Then again, part of bitcoin’s value proposition is that it’s scarce, with a capped supply of 21 million.

The tokenomics

The tokenomics of Worldcoin are fuzzier.

Jesse Walden, an early investor in the project and general partner at Variant, acknowledges that “who pays” is a good question to ask, but says “I don’t know that there’s a single definitive answer right now, or that there needs to be.” The way he sees it, “Most startups don’t have a business model figured out at the beginning,” and they typically focus on growth, and the growth of the network eventually begets use cases and value.

Altman has a more pragmatic answer. In the short term, Altman says, “The hope is that as people want to buy this token, because they believe this is the future, there will be inflows into this economy. New token-buyers is how it gets paid for, effectively.” (If you’re feeling less charitable, you could view that as just another flavor of “Number Go Up” crypto speculation.)

The long-term and grander vision, of course, is that the fruits of AGI will confer financial rewards that can be bestowed upon humanity. (Hence the name of Worldcoin’s parent company – Tools for Humanity.) How that happens is anyone’s guess. “Eventually, you can imagine all sorts of things in the post-AGI world,” Altman says, “but we have no specific plans for that. That’s not what this is about, at this phase.”

The world is going to get driven forward. As the world gets driven forward, the playing field shifts

There are few people on the planet who are better equipped to envision a post-AGI world than Altman, who sits at a curious intersection between these two AI projects. He’s arguably the most central player in the development of AI, and he’s now the co-founder of a project intended, at least in part, to serve as a check on the demons of AI. Although he doesn’t see it like that. “I get the appeal of framing the story as ‘creating the problem here, solving the problem there.’ That’s not how I think about it,” he says.

Here’s the way he frames it. “The world is going to get driven forward. As the world gets driven forward, the playing field shifts,” Altman says. “And there are a whole bunch of things that should happen, but it’s not like problem-solution. It’s more like a co-evolving ecosystem. I don’t think of one as a response to the other.” (I’ll be the first to admit that Altman can run circles around me intellectually, and he strikes me as earnest and well-intentioned, but I do find this answer befuddling. It does, in fact, seem like one project is a clear response to the other.)

I ask Altman the same question I posed to Blania in our first conversation: What does the world look like if Worldcoin fully succeeds, and everything breaks right? Let’s say billions of users have been onboarded and the financial gains from AGI are fairly distributed to all. What’s that future like? This is another way of asking, in a sense, what’s the point of all of this?

“I think we all just get to be the best version of whatever we hope for,” Altman says. “More individual autonomy, and agency. More time. More resources to do things.” He speaks quickly and without hesitation; these are ideas he’s been mulling for years. “Like with any technological revolution, people figure out amazing new things to do for each other…But it’s a very different, and much more exciting world.”

And the biggest risks and challenges to fulfilling that vision? Altman thinks it’s “premature to talk about the big challenges,” but acknowledges that OpenAI and Worldcoin “are a very long way from working,” and that “we have a mountain of work in front of us.”

That mountain of work includes rolling out the Orb in the field. And this is where things get dicey.

The field

The goal of scanning eight billion sets of eyeballs is almost hilariously ambitious. For perspective, it would be a daunting logistical challenge to give everyone on the planet a free handful of candy, even without any biometric strings attached. How do you reach remote areas? How do you safely transport the precious Orbs? How do you explain this complicated relationship between the looming powers of AGI and the need for UBI and the merits of cryptocurrency?

The pitch is essentially, “Hey, get some free crypto!”

That message has been refined and massaged and nuanced over time, but that’s the basic hook: You can sign up for some free crypto, and this Orb is how we prove you haven’t signed up anywhere before.

Consider Blania’s very first field-test, which sounds like something out of a Judd Apatow comedy. At a park in Germany, Blania took the Orb and looked for people to approach. He spotted two young women. Should he talk to them? The Worldcoin team watched from a distance. (In the Berlin office, on his phone, Blania finds a photo someone took of the scene and shows it to me; it has the vibe of a guy at a bar, nervous, mustering the courage to flirt.)

Back in the German park, they were still in the early “bitcoin project” days. So Blania approached one of the women, he showed her the Orb, and he says that this can help give her free bitcoin. “The only thing this device does,” he told her, “is make sure you only get it once, but you get bitcoin and you should be excited about that.”

The woman had simple response. “Are you crazy?”

She opted not to get her iris scanned, but all was not lost, as her friend volunteered.

Blania says with a half-smile, “I think she just found me cute, actually.”

That’s not so surprising; Blania is a handsome guy. He’s also charming and intelligent and can speak clearly and convincingly about the benefits, nuance and raison d’être of Worldcoin (who wouldn’t be impressed?). But how do you scale Alex Blania? Perhaps if Blania could be cloned, he could personally onboard all eight billion people. (I humbly suggest “cloning” as another Sam Altman startup.)

But in our non-cloning reality, in the beginning, Blania and a small team just lugged the Orb around the streets of Berlin, showing it to people and trying to explain it on the fly. “This was literally the early playbook,” Blania says. “People would approach us, because it’s this shiny chrome ball and people would be like, ‘What the hell is that?’”

These were the early Orbs that spoke to the user in a strange robotic voice, instructing them to move closer or farther away or maybe to the left. (Since then, the team has made a flurry of inventions to automate the process.) The robot-voice baffled and amused onlookers, and sometimes they’d laugh and take Orb selfies.

Neo-colonialism issues

Less amusing were the early attempts to recruit users in Nairobi, Sudan and Indonesia. In April of 2022, MIT Technology Report published a 7,000-word feature titled “Deception, exploited workers, and cash handouts: How Worldcoin recruited its first half a million test users.” The writers argued that despite the project’s lofty ambitions, “so far all it’s done is build a biometric database from the bodies of the poor.”

The blistering report chronicles a shoddy operation rife with misinformation, data lapses and malfunctioning orbs. “Our investigation revealed wide gaps between Worldcoin’s public messaging, which focused on protecting privacy, and what users experienced,” write Eileen Guo and Adi Renaldi. “We found that the company’s representatives used deceptive marketing practices, collected more personal data than it acknowledged, and failed to obtain meaningful informed consent.”

I ask both Blania and Altman about the damning reports. “The first big thing to understand is that this article came out before the company came out of Series A,” says Blania. He admits that’s no excuse, but emphasizes that the project was in its infancy and that since then, “literally everything has changed,” with tighter operations and protocols in place. “I cannot think of a single thing that was the same,” he says. The counter to this counter, of course, is that it’s the very possibility of mistakes like this – however well-intended the team – that make people queasy about sharing their biometric data.

Blania also bristles that the piece was framed as (in his words) “a colonialist approach of trying to just sign up poor people all over the world.” He says this is misleading, as over 50% of the signups, at the time, came from wealthier spots like Norway and Finland and European countries. Their goal was to test sign-ups in both developed and developing regions, in hot and cold climates, city and rural, to better understand what works and what doesn’t.

Altman sees the missteps as natural growing pains for any large-scale operation. “For any new system, you will face some initial fraud,” Altman says. “That’s part of the reason we’ve been doing this for a long time now [in this] slow beta period. To understand how the system can face abuse, and how we’re going to mitigate against that. I don’t know of any system at this scale, and at this level of ambition, that has no fraud issue at all. We want to be thoughtful about that.”

One of these mitigating actions was to change the way that Orb operators are compensated. There are currently between 200 and 250 active Orbs in the field, and roughly two dozen Orb operators who each hire their own sub-teams of on-the-ground helpers. In the beginning, Worldcoin paid operators simply for raw number of sign-ups, which led to some sloppy and shoddy practices.

Blania says that operators are now incentivized not just by the quantity but also the quality of the signups, and how well users understand what is happening; weeks after the Orb scan, the operators will be paid more if users are actually using the Worldapp. (The main way you “use” the Worldapp right now is claiming your one weekly worldcoin.) I spoke with two operators in Spain, Gonzalo Recio and Juan Chacon, who largely corroborated that new protocol. But whether this process is being tightly followed around the globe remains an open question.

I don’t know of any system at this scale, and at this level of ambition, that has no fraud issue at all

How can people trust that Worldcoin has really addressed the problems? Altman hears the questions, and he knows he’s unlikely to win over the skeptics. He doubts he has any answers that will satisfy, and he seems okay with that. He believes the more persuasive answers will come not from him or Blania or the company, but from the early users of Worldcoin. “You can go try to answer a bunch of questions and do all these things, but that’s not really how it works,” says Altman.

“What really works,” he says, “is the first million people, the early adopters, the people leaning forward – convince the next 10 million. Then that next 10 million is closer to the normies. And they convince the next 100 million. And those are really the normies that convince the other few billion.”

The policy and the future

In our very first conversation, Blania told me that if WorldID and the UBI of Worldcoin is fully adopted at scale, this would be “probably one of the most profound technological shifts that has ever happened.” If this is indeed the case, wouldn’t that create a new complicated set of legal, policy and even existential questions that governments need to reckon with?

As I finish up my session in the Berlin office, one final question keeps gnawing at me. It almost feels like the project is so ambitious, so wild, so transformative – at least in theory – that the Powers That Be haven’t fully considered the consequences. If humanity is compensated not by the sweat of its labor, but instead by the largesse from AGI, wouldn’t that represent a fundamental shift in the way the world is structured? And wouldn’t governments insist on regulating this? Assuming the answer is yes, how is Worldcoin tackling that question?

Blania leans back in his chair, stretches out his long legs and thinks for a moment. “This is obviously a major discussion point,” he says. “I’ll start with what’s top of mind right now. And what is top mind is actually way less sophisticated than all the things you just mentioned.” What they’re focused on, says Blania, is simply the basic meat-and-potatoes of regulatory uncertainty in the U.S. Worldcoin is “very likely to be the largest onboarding into crypto the world has ever seen,” says Blania. “So if you don’t like crypto…”

Altman pushes back on the idea that policy-makers are clueless or have their heads in the sand. “I went to like 22 countries and met with many world leaders, and much more than I thought, people get this and are taking it super seriously,” he says. (It’s unclear if by “this” he’s referring to the particular ambitions of Worldcoin, or the broader challenges posed by AI.) “I’m now spending an increasing amount of my time not on technical stuff,” he says, “but on policy challenges.” Ultimately, Altman says that “For the world to get to a good place through all of this, it has got to be a two-part solution, of tech and policy together. And the policy part, in some sense, may turn out to be more difficult.”

Roadblocks from policy is one risk to Worldcoin. Not scaling quickly enough is a risk to Worldcoin. More missteps in the field, like the ones highlighted in the MIT Technology Report, pose another risk. Or a potential breach of iris data. Or a failure of the tokenomics. Or an erosion of trust that kneecaps future signups. Or logistical challenges for bringing the Orb into trickier corners of the world. Or tech and manufacturing glitches. Or revelations that the Orbs have somehow been compromised. (As Buterin noted, “the Orb is a hardware device, and we have no way to verify that it was constructed correctly and does not have backdoors.”)

Or, maybe Worldcoin is never worth more than a few pennies, so no one cares. There are many, many risks on the impossibly long road to Worldcoin’s widespread adoption, and the project remains a moonshot.

But the biggest risk, as the company’s braintrust sees it, is not a risk about Worldcoin itself. The most chilling risk, to them, is that something like a biometric WorldID will be developed, only not in a way that’s open or privacy-preserving.

Altman’s original logic, which he articulated well before ChatGPT went mainstream, remains compelling: Eventually AI will get so good that it can easily pretend to be human, so we’ll need a way to prove our humanity. Perhaps biometric proof is inevitable. Who should be the stewards of that solution? “Something like WorldID will need to happen,” says Blania. “You will need to verify yourself online. Something like that will happen. And the default path is that it’s not online by nature, it’s not privacy-preserving and it’s fragmented by government and countries.”

That non-privacy version of biometric vetting, to Blania, is the real Black Mirror episode. “That’s the default path,” he says. “I think Worldcoin is the only other path there is.”

Edited by Ben Schiller.